I would like to propose a theory if I may:

Stories are like triangles.

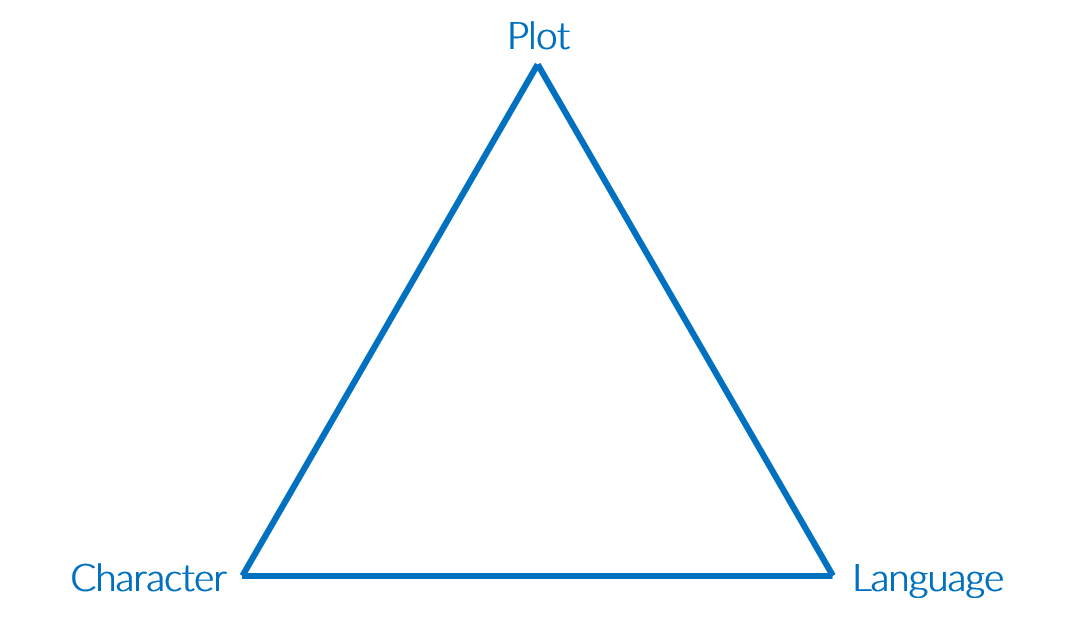

How I see it, a story at its simplest is made up of three ingredients – plot, character, and language – and the amount of emphasis we give to any one of those things creates a different-shaped triangle.

If we give equal weighting to each element then we have an equilateral triangle:

Or we might push an individual element over and above the others:

There are multiple different triangles we could come up with that push one element of a story over the others, and I think the shape of our story-triangles says a lot about (a) who we are as readers, (b) who we want to be as writers, and (c) what sort of story we are wanting to create.

Writing like any artform is highly subjective. As readers, some of us need a fast-paced plot to keep us intrigued. For some of us, character is the most essential element. There are perhaps only a handful of people who would say that language is the most important part of a story (please feel free to prove me wrong in the comments!), but there are still plenty (myself included) who feel that a story lives or dies as much on the language used as the other two elements.

Having an idea of these different types of story-triangle can, I think, help us get more of a grip on subjectivity. If a reader’s triangle is an equilateral, looking for at least a score of 6 out of 10 for each element, then we could write a wonderful story that really pushed character and language but neglected plot, and the story probably wouldn’t be that reader’s cup of tea:

If we get mathematical for a second, we can maybe work out that the writer triangle adds up to 19 and the reader triangle only adds up to 18 – so perhaps a stronger story overall, but the problem for this particular reader will always come back to plot.

Of course, plot itself has several strands, all of which will have more or less bearing on any particular story. Within plot, you have “originality”, “premise”, “situation”, “trigger”, “conflict”, “barriers”, “resolution”, and “focus” to name a few ingredients. Character meanwhile comprises stuff like “dimensions”, “relatability”, “authenticity”, “motivation”, “relationships”, “emotional journey” and “resonance”. Within language you might have “word choice”, “voice”, “imagery”, “rhythm”, “flow” as well as “pacing”, “structure” and “form”.

That’s a lot of plates for a writer to be spinning, and that’s why I find this idea of a triangle quite useful. It gives us a template for what we actually want to achieve with a story. If we want to take the red writer triangle above and make it big enough for the blue reader triangle to fit inside then we probably need to stretch our story-triangle in a more plotty direction, thinking about those eight elements of plot (there are others!) I’ve mentioned above and what this particular story might need in order to make the story-triangle bigger.

But let’s not stop there. Let’s add another element to our increasingly complex equation. The outside lines of the triangle, the ones which connect character, language and plot are probably better if we visualise them as arrows, something to imply how we want each element to influence the other.

In most stories, we want language to serve both character and plot. For example, if the story is set in the countryside and our narrator / main character is an apiarist then we probably want the tone of voice and the imagery to reflect that.

The relationship between character and plot is often more complex. Sometimes, we want the plot to be subservient to the character. Sometimes, we want the character to be subservient to the plot. And sometimes we want more of a symbiosis between the two.

Finally, I think we need to consider that story-triangles come in every single colour under the sun. We have green triangles, and aquamarine triangles, and cherry-blossom-on-a-Tuesday triangles, all of which represent different genres – historical, romantic, sci-fi, fantasy, detective, mystery, psychological etc. So, not only do we want our triangle to be a certain shape with the three sides pointing in the correct direction to best serve the story, but we also want to paint that triangle in the most appropriate colour.

Coming back to subjectivity for a second, if a reader only likes stories that are somewhere on the spectrum between blue and yellow, they probably won’t enjoy stories from a writer whose genre encompasses the space between purple and red no matter how perfectly the shape of the triangle fits their particular ideal:

The genre of a story will also, to a certain extent, affect the story-triangle’s shape. Literary stories tend to have a greater emphasis on the character side of the triangle. Action adventures are by definition more plotty. I would suggest that the most language-dominant genre is probably humour, and humorous stories might be the only ones where the “influence” arrows between language and character and language and plot have a chance of flipping around to point away from language rather than towards it.

And then…

Yes, there’s a “finally, finally” point to this equation: the best story-triangles aren’t two-dimensional things – instead, they are prisms:

But I’ll leave the exploration of a story’s prismatic depths for another time. For now, let’s revert to the idea of a story as a triangle. And here’s a quick exercise you might try:

Take a story you’re currently working on or something from your archives that you’ve been trying to bash into shape.

Draw the triangle you want to achieve. What does it look like? (I would suggest aiming for something that isn’t a perfect 10 | 10 |10 because perfection is pretty much unachievable in art).

Now think about the triangle you currently have. Draw that next to your “dream” triangle. Which part of the triangle needs stretching out? (Just choose one from “plot”, “character”, “language” so you can focus firmly on that).

Next, write down one or two of the strands that build that part of the triangle (e.g. “motivation” / “emotional journey”) to hone your focus even further.

Then draw in the “influence” arrows – what direction do they point?

Finally, choose a colour to represent the genre of your story and shade the triangle in.

Once you have all of that, return to your story with the sole intention of stretching the shape of your story-triangle towards your one chosen element. What might you add or change to achieve that?

Hopefully, that hasn’t all brought you out in hives remembering secondary school maths lessons and incomprehensible gibberish like “tangents” and “cosines” and “a2 + b2 = c2”.

Hopefully, it’s useful.

Hopefully, it gets you thinking about the sort of stories you’re aiming to write and whether a particular story needs to be stretched in a particular way.

Nice. And nice triad.

What an extraordinary and thought provoking way of looking at fiction! Sometimes I have wondered if the best geometrical analogy is not a figure or shape, but a grid. The Cartesian plane is a grid; this can be extended to three axes in multivariate math; and in relativity, it is extended even further. A multi dimensional fictional space were you can locate the bits of a story as points.